“Then let them consider the sorrow and suffering hidden behind these deformities. The woman with the aging face whose mind and body are still alert. The young girl deprived of her right to marriage and motherhood by unsightly scars, a hooked or flattened nose. The boy who is the butt of ridicule because of outstanding ears. The chinless, the grotesque and the victims of twisted features. To these the plastic surgeon now opens the door to a new life with an art in which there is no longer any uncertainty.”

— Henry J. Schireson, As Others See You (1938)

The History of Facelift – Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Nineteen-Century Foundations

- Proto-Facelifts and the Birth of Rhytidectomy (1900-1919)

- The Classic Cutaneous Facelift Era (1919-1960s)

- SMAS and Subfacial Revolution (1060s-1980s)

- Deep Plane and Midface Era (1980s-2000s)

- The Facial Volume Revolution with the Modern Facelift

- Contemporary Facelifting (2000s-Present)

- The Future & Surgical Art of Facelift: From Experiments to Refinements

Note from the Author:

This is a living and continually evolving work in progress. As additional historical documents and verified sources become available, this page will be thoughtfully updated. We invite you to bookmark it and revisit for future additions and refinements.

Abstract

The facelift, or rhytidectomy, is frequently mischaracterized as a late-twentieth-century cosmetic invention driven by celebrity culture. The history of facelift represents more than a century of continuous surgical evolution rooted in reconstructive surgery, wartime innovation, anatomical discovery, and shifting cultural ideals. This manuscript traces the development of facelifting from nineteenth-century reconstructive foundations through early cosmetic experimentation, the SMAS revolution, the deep-plane era, and contemporary volumetric and ligament-based rejuvenation. By integrating the contributions of all major historical figures and technical schools, this review situates the facelift as one of the most anatomically sophisticated and socially significant operations in modern surgery

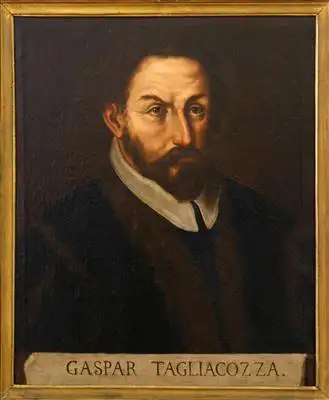

Long before the modern facelift became synonymous with facial rejuvenation, plastic surgery itself emerged from a far deeper and more ambitious medical tradition: the restoration of the human form. One of the earliest architects of this vision was the Italian surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi, whose 1597 treatise De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem described ingenious techniques for reconstructing noses and faces using transplanted tissue from the arm.

Tagliacozzi’s work established the central philosophical principle that would guide plastic surgery for centuries and that surgical intervention could restore not only anatomy but dignity. From these reconstructive origins, plastic surgery evolved into a remarkably innovative specialty, particularly in the hands of surgeons who applied its principles to the aging face and body. As anatomy, anesthesia, and surgical technique advanced, the tools originally designed to repair trauma and deformity were gradually adapted to aesthetic refinement, giving rise to the most sought-after cosmetic procedures of the modern era. Among these, the facelift stands as the clearest embodiment of plastic surgery’s unique ability to blend science, artistry, and human psychology in the pursuit of a more youthful appearance.

Nineteenth-Century Foundations

Facelifting would not have been possible without the intellectual and technical foundations laid by nineteenth-century plastic surgery, and the decisive figure in this transition was Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach. In 1845, Dieffenbach published Die operative Chirurgie, a monumental surgical treatise that helped redefine the scope of operative medicine. At a time when surgery was largely associated with life-saving intervention, trauma, or amputation, Dieffenbach argued that surgical repair of form, particularly of the face, was a legitimate and necessary medical pursuit. His work bridged reconstructive necessity and aesthetic intention, dissolving the rigid boundary between function and appearance.

Dieffenbach devoted extensive attention to facial deformities, scars, and disfigurement resulting from trauma, disease, or congenital conditions. Importantly, he did not frame these problems solely in terms of physical impairment but acknowledged the profound social and psychological consequences of facial appearance. By doing so, he normalized the idea that improving facial form could restore dignity and social integration, not merely anatomy. This philosophical shift was critical: it allowed surgeons to justify operating on the face even when function was preserved, provided that appearance was compromised.

Technically, Dieffenbach advanced flap design, tissue handling, and staged reconstruction, emphasizing precision, symmetry, and minimal visible scarring. These are the principles that would later become central to aesthetic surgery. Conceptually, he legitimized surgical intervention for appearance within academic medicine, publishing openly and systematically rather than relegating such procedures to private or clandestine practice. By establishing facial repair and aesthetic improvement as ethically defensible and scientifically grounded, Dieffenbach created the conceptual space in which cosmetic procedures, including facelifting, could eventually emerge. Without this normalization of appearance-focused surgery, the later development of elective facial rejuvenation would have lacked both professional legitimacy and intellectual precedent.

In the United States, John H. Woodbury played a pivotal role in blurring the boundary between medicine, commerce, and beauty long before facelifting became a recognized surgical procedure. Between roughly 1870 and 1909, Woodbury built a nationwide network of cosmetic institutes that openly advertised wrinkle removal, facial rejuvenation, and the preservation of youthful appearance. Operating in an era when most physicians were reluctant to associate themselves with aesthetic improvement, Woodbury unapologetically marketed appearance-altering services directly to the public, helping normalize the idea that facial aging was a problem that could and should be treated.

Woodbury’s enterprises combined topical preparations, mechanical devices, massage techniques, and minor procedures that promised smoother skin and restored youth. While these methods were crude and largely ineffective by modern scientific standards, their importance lies less in technical merit than in cultural impact. Woodbury demonstrated that demand for facial rejuvenation was not confined to elite circles or private surgical practices; it existed broadly across American society and could sustain a large-scale commercial infrastructure. His clinics and widely distributed advertisements reframed facial aging as a modifiable condition rather than an inevitable fact of life.

By positioning rejuvenation as both desirable and attainable, Woodbury helped shift public perception decades before the advent of anatomically based facelifting. Surgeons who later developed formal facelift techniques did so in a cultural environment already conditioned to accept—and seek—intervention for facial aging. In this way, Woodbury’s legacy is not surgical but sociological: he proved that the desire for youthful facial appearance predated scientific facelifting and that a receptive public audience was already in place, waiting for medicine to catch up.

Proto-Facelifts and the Birth of Rhytidectomy (1900–1919)

At the turn of the twentieth century, facial rejuvenation existed in an uncertain space between reconstructive necessity, private experimentation, and social taboo. There was no established operation called a “facelift,” no standardized anatomy to guide it, and no academic framework to legitimize it. Yet the desire to surgically address facial aging had already emerged, driven by cultural pressures, changing concepts of beauty, and the growing confidence of surgeons willing to operate beyond strict functional indications. The period from 1900 to the end of World War I represents the proto-facelift era—a formative phase in which early excisional techniques, evolving anatomical insight, and divergent European and American approaches collectively gave rise to what would later be defined as rhytidectomy.

During these years, surgeons began to test fundamental questions that would shape the future of facelifting: Could facial aging be surgically corrected? Where could incisions be hidden? How much tissue could safely be mobilized? And, critically, was facial rejuvenation a legitimate surgical pursuit at all? The answers emerged unevenly—through published case reports, private practices, and wartime reconstruction—but together they established the conceptual and technical foundations upon which modern facelift surgery would be built.

The First Facelift

The first published facelift was performed in 1901 by Eugen Holländer in Berlin, marking a foundational moment in aesthetic facial surgery. Holländer described the excision of an elliptical segment of skin positioned just anterior to the ear, relying on skin tension alone to elevate the cheeks and oral commissures. At a time when aesthetic surgery was viewed with skepticism and often relegated to private practice, Holländer’s willingness to formally document and publish the procedure gave legitimacy to facial rejuvenation as a surgical endeavor. His method reflected the prevailing surgical philosophy of the era: aging was understood primarily as skin laxity, and correction was achieved through direct skin removal rather than manipulation of deeper structures.

Although anatomically crude by modern standards, Holländer’s approach established several enduring principles. He demonstrated that facial aging could be surgically addressed with predictable improvement, that incisions near the ear could be concealed with careful planning, and that aesthetic procedures could be described in the same academic language as reconstructive operations. For decades, facelifts remained variations on Holländer’s original concept, limited skin excision with modest undermining, largely because surgeons were cautious about facial nerve injury and lacked a detailed understanding of facial anatomy. In this sense, Holländer did not merely perform the first facelift; he defined the conceptual boundaries of early facelifting, shaping the procedure’s evolution well into the mid-20th century.

Between 1906 and 1916, Erich Lexer independently advanced facial rejuvenation surgery beyond simple skin excision by introducing wider undermining and deliberate repositioning of facial tissues. Working within the broader framework of reconstructive surgery, Lexer approached facial aging not merely as redundant skin but as a problem of displaced and sagging soft tissues. His operations involved elevating larger skin flaps, allowing the surgeon to redistribute tension more evenly and achieve longer lasting and more natural contours than earlier, limited excisions.

Lexer’s willingness to undermine extensively marked a conceptual shift. Rather than relying on tight skin closure near the ear, he recognized that mobilizing tissue over a broader area reduced distortion of the hairline and auricle while improving the cheek and jawline. This approach anticipated later principles of rhytidectomy: strategic undermining, controlled redraping, and tension placed away from visible incision lines. Although Lexer did not manipulate deeper fascial layers as modern surgeons do, his techniques demonstrated an early understanding that facial rejuvenation required movement, not merely removal, of tissue.

Because of these innovations, some historians regard Lexer, not Holländer, as the first true facelift surgeon. Lexer’s procedures more closely resemble modern rhytidectomy in both intent and execution, emphasizing anatomical repositioning rather than surface tightening. His work bridged the gap between rudimentary cosmetic skin excisions and the anatomically informed facelift techniques that would emerge later in the 20th century, securing his place as a pivotal figure in the evolution of facelift surgery.

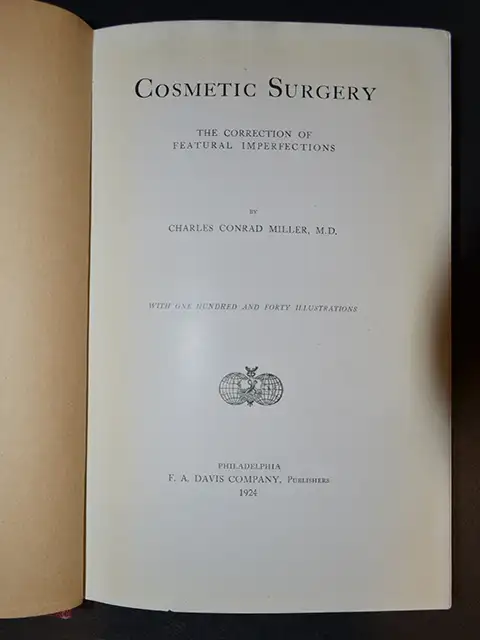

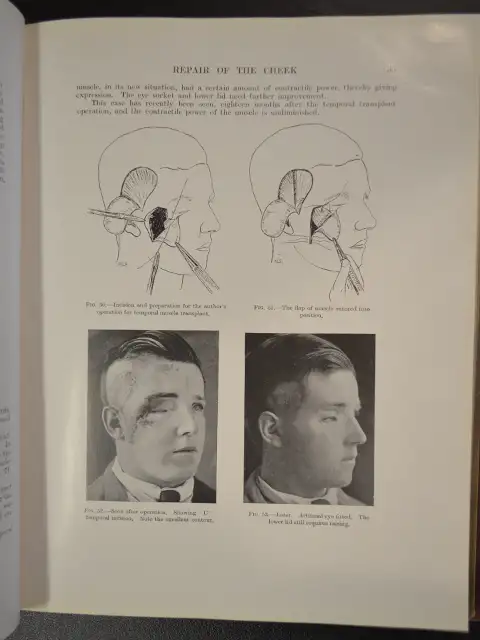

Simultaneously, in the United States, Charles Conrad Miller published Cosmetic Surgery: The Correction of Featural Imperfections (1907/1908), a landmark work that formally established cosmetic surgery as a distinct and intellectually rigorous field. Spanning 263 pages and illustrated with 140 detailed drawings, the book was the first comprehensive textbook devoted entirely to aesthetic procedures of the face and body. At a time when cosmetic surgery was often dismissed as vanity-driven or ethically questionable, Miller framed it as a legitimate medical discipline grounded in anatomy, function, and careful observation.

Miller’s most forward-thinking contribution lay in his conceptualization of facial aging. Rather than viewing wrinkles as purely passive results of gravity or skin laxity, he described aging as a dynamic, physiologic process driven by repeated muscular contraction over time. He identified specific facial muscles as the generators of characteristic expression lines and proposed surgical interventions aimed at weakening or interrupting these muscles to soften wrinkles. This muscular theory of aging represented a profound departure from skin-only approaches and anticipated, by nearly a century, the fundamental logic behind neuromodulator therapy.

Although Miller’s techniques were surgical rather than injectable, his ideas laid crucial intellectual groundwork. He recognized that durable facial rejuvenation required modifying the forces that create wrinkles, not merely excising their visible results. His emphasis on muscle function, facial expression, and individualized treatment planning resonates strongly with modern aesthetic philosophy. In this sense, Miller stands not only as an early cosmetic surgeon but as a conceptual pioneer whose insights foreshadowed some of the most influential non-surgical facial rejuvenation strategies in contemporary practice.

Remembered almost exclusively for the notorious Fannie Brice rhinoplasty, Dr. Henry J. Schireson’s cosmetic practice extended well beyond nasal surgery. Mentored by a famous German surgeon, Dr. Jacques Joseph (Nasenplastik), Schireson was active in New York during the first two decades of the 20th century, approximately 1905 to 1918. Schireson operated at a moment when public demand for facial rejuvenation was growing rapidly, yet before facelifting had been standardized or academically legitimized. Like many early American cosmetic surgeons working outside university centers, he offered a menu of appearance-altering procedures aimed largely at performers, socialites, and patients concerned with facial aging or socially stigmatized features.

Within this commercial cosmetic milieu, Schireson is believed to have performed rudimentary facial rejuvenation procedures between 1908 and 1915, placing him among the earliest American practitioners to address facial aging surgically. These operations were not facelifts in the modern sense but consisted of limited skin excisions near the hairline or preauricular region, designed to reduce wrinkles and sagging of the cheeks and lower face. Tension was applied directly through skin removal rather than deeper tissue repositioning, reflecting the prevailing understanding of aging at the time.

Although he did not develop new principles of facial anatomy, nor did he publish systematic techniques. Instead, he demonstrated that patients were willing to undergo, and surgeons were willing to offer facial rejuvenation procedures well before the specialty was professionalized. In this sense, Schireson stands as an early, commercially driven precursor whose work underscored both the demand for facelifting and the urgent need for the anatomical rigor that later surgeons would provide.

Schireson’s facelift-related procedures lacked anatomical sophistication and long-term durability. However, they represent an important transitional phase in which American surgeons began applying operative methods to facial aging outside reconstructive necessity.

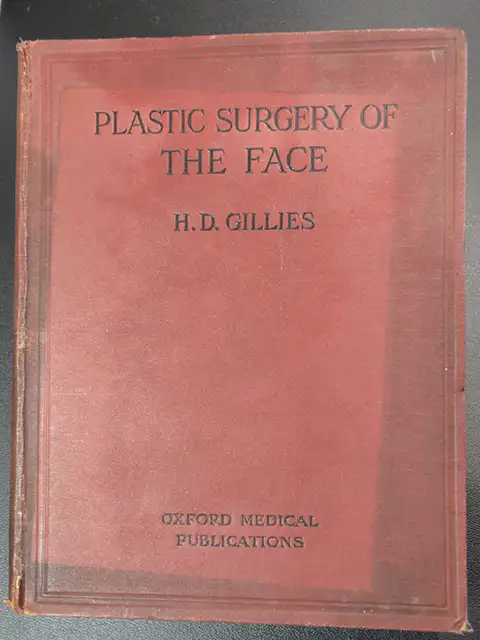

During World War I, the unprecedented scale and severity of facial injuries forced surgeons to confront problems that had never before been encountered in such volume or complexity. Trench warfare, high-velocity bullets, and explosive shrapnel produced catastrophic destruction of the jaws, cheeks, lips, noses, and eyelids, leaving thousands of young soldiers alive but socially and functionally devastated. It was in this crucible that Johannes Esser and Sir Harold Gillies fundamentally transformed the practice of facial surgery. Esser introduced innovative skin-graft inlay and rotation flap techniques, demonstrating that large segments of damaged facial tissue could be replaced with living, vascularized skin rather than scar alone. Gillies expanded these principles into a systematic approach to facial reconstruction, pioneering the use of tubed pedicle flaps, staged operations, and meticulous tissue planning to rebuild complex three-dimensional facial structures. Rather than performing single heroic procedures, Gillies recognized that the face could be reconstructed gradually, in carefully sequenced stages that preserved blood supply and allowed tissues to survive and adapt.

Gillies’ landmark 1920 textbook, Facial Plastic Surgery, codified this wartime experience into a coherent surgical doctrine, illustrating how flaps, grafts, and layered reconstruction could be used to restore facial form. Although written for reconstructive purposes, the principles laid out in this work precise incision planning, respect for tissue vascularity, three-dimensional contouring, and the use of hidden scars all became the technical foundation of modern aesthetic surgery. The facelift would later draw directly from Gillies’ philosophy: that the face is not merely skin to be tightened, but a complex anatomical structure whose appearance can be transformed only through thoughtful manipulation of deeper tissues.

The Classic Cutaneous Facelift Era (1919–1960s)

With the end of World War I, facelifting entered a period of consolidation and standardization. What had previously been experimental and heterogeneous began to coalesce into reproducible surgical techniques centered on skin excision, incision design, and controlled redraping. From Raymond Passot’s formalization of preauricular incisions to the widespread adoption of long skin flaps under tension, this era defined the classic cutaneous facelift—a procedure that dominated facial rejuvenation for nearly half a century. Although limited by its reliance on skin alone, this period established facelifting as a legitimate, teachable surgical operation and set the stage for the anatomical breakthroughs that would later transform the field.

In 1919, Raymond Passot published what is regarded as the first standardized facelift technique, marking a critical turning point in the evolution of facial rejuvenation surgery. Passot formalized the use of S-shaped preauricular incisions, deliberately designed to follow natural skin creases in front of the ear, allowing scars to be better concealed while providing sufficient access for controlled skin excision. Unlike earlier, ad hoc approaches, Passot’s method was systematic and reproducible, transforming facelifting from an improvised cosmetic maneuver into a defined surgical operation.

Passot’s technique reflected a maturing understanding of facial aesthetics and surgical planning. By standardizing incision shape and placement, he enabled more predictable elevation of the cheeks and softening of nasolabial folds while minimizing distortion of the hairline and ear. Although his approach remained focused on skin excision rather than deep tissue manipulation, it introduced the concept that facelifting required intentional design, not merely removal of redundant skin. This emphasis on planning and symmetry distinguished Passot from earlier practitioners and positioned his work as a template for subsequent refinement.

The influence of Passot’s 1919 publication extended beyond France and directly shaped contemporaneous developments in Central Europe. German surgeons adapted and elaborated on his excisional framework through procedures such as Hangewangenplastik and melomioplasty, cheek-lifting operations aimed at correcting sagging of the midface and jowls. These techniques preserved Passot’s core principles of strategic incision placement and controlled skin removal while expanding the aesthetic goals to include improved facial contour and balance. In this way, Passot’s standardized facelift served as the conceptual foundation upon which early 20th-century European surgeons built increasingly sophisticated excisional rejuvenation procedures, firmly establishing facelifting as a recognized surgical discipline.

Suzanne Noël was one of the first female plastic surgeons and a central figure in popularizing cosmetic facelifting in France during the early 20th century. Practicing in Paris in the 1920s, Noël performed facelifts and other aesthetic procedures at a time when cosmetic surgery was still viewed with suspicion and when women were excluded from surgical authority. Her work helped normalize facial rejuvenation as a legitimate medical service and broadened its acceptance beyond elite or clandestine circles into mainstream French society.

In her influential 1926 book La chirurgie esthétique: son rôle social, Noël advanced a radically progressive argument: that aesthetic surgery, including facelifting, could function as a form of female autonomy. She framed surgical beauty not as vanity, but as a practical tool through which women could maintain social relevance, economic independence, and professional opportunity in a society that often marginalized aging women. By explicitly linking facial rejuvenation to social survival and self-determination, Noël repositioned the facelift as an instrument of empowerment rather than indulgence.

Noël’s contribution was not limited to ideology. She emphasized discreet incision placement, natural results, and rapid recovery, as principles that aligned with the needs of working women and professionals. Her ability to integrate technical skill with social philosophy distinguished her from many contemporaries and helped shift the cultural narrative surrounding cosmetic facelifting. Through both her surgical practice and her writings, Suzanne Noël expanded the meaning of the facelift, transforming it from a purely technical procedure into a socially and politically resonant act, and securing her place as one of the most influential figures in early aesthetic surgery.

During the 1930s–1950s, surgeons including Raymond Passot and Hippolyte Morestin refined facelift surgery through increasingly deliberate incision placement and more systematic skin redraping. Building on earlier excisional techniques, these surgeons focused on improving scar concealment around the ear and hairline while expanding the extent of skin undermining. Their work reflected a growing consensus that predictable rejuvenation required larger, carefully elevated skin flaps rather than small, localized excisions.

By the mid-20th century, these refinements had coalesced into what became known as the “classic facelift.” This operation relied on long skin flaps elevated widely across the cheek and jawline, then redraped and tightened under significant tension before excess skin was excised. The method was undeniably effective at smoothing wrinkles, sharpening the jawline, and reducing jowling, and for the first time allowed surgeons to produce dramatic, immediately visible rejuvenation. As a result, the classic facelift became the dominant approach for several decades and was widely taught and replicated.

However, the very features that made the classic facelift powerful also revealed its limitations. Because correction depended almost entirely on skin tension rather than deeper anatomical support, results often appeared pulled or mask-like, with telltale signs such as widened scars, distorted hairlines, and unnatural ear position. Longevity was also limited, as skin alone could not reliably counteract gravitational descent over time. Nevertheless, the classic facelift represented a crucial evolutionary stage: it standardized facial rejuvenation surgery, established reproducible techniques, and clarified the shortcomings of skin-only lifting that would later drive the development of different types of facelift such as the deeper-plane and anatomically based facelift methods in the latter half of the 20th century.

SMAS and Subfascial Revolution (1960s–1980s)

By the mid-20th century, the limitations of skin-only facelifting had become increasingly apparent, prompting surgeons to look beneath the surface for more durable and anatomically faithful solutions. The period from the 1960s through the 1980s marked a fundamental reorientation of facelift surgery—from cutaneous tightening to deep structural repositioning. Advances in anatomical understanding, driven by reconstructive surgery, revealed that facial aging was governed by the descent and deformation of deeper soft-tissue layers. This era ushered in the subfascial and SMAS revolutions, permanently transforming facelifting into an anatomically based operation and establishing the principles that underpin modern facial rejuvenation.

A major conceptual leap in facelift surgery occurred in 1969, when Tord Skoog introduced subfascial facelifting, fundamentally altering how surgeons understood and treated facial aging. Rather than relying on skin tension alone, Skoog elevated and repositioned the deeper fascial layers of the face, recognizing that sagging of underlying tissues, not just skin laxity, was the primary driver of age-related facial descent. This shift marked the first systematic attempt to anchor facelift correction to durable anatomical structures.

Skoog’s technique involved dissecting beneath the superficial facial fascia and lifting the composite soft-tissue envelope as a unit. By redistributing tension to deeper layers, he reduced the unnatural “pulled” appearance characteristic of classic skin-only facelifts and achieved results that were both more natural in contour and longer lasting. Importantly, this approach also decreased reliance on excessive skin tightening, minimizing scar widening and distortion of the hairline and ear.

Although technically demanding and not immediately adopted by all surgeons, Skoog’s subfascial facelift represented a turning point in facial rejuvenation surgery. It reframed the facelift as an operation of anatomical repositioning rather than surface tightening, laying the intellectual groundwork for subsequent developments such as SMAS manipulation, deep-plane, and composite facelift techniques. In retrospect, Skoog’s 1969 contribution stands as a foundational moment in the transition from excisional to anatomically based facelifting.

French craniofacial pioneer Paul Tessier profoundly advanced surgical understanding of facial soft-tissue planes, particularly through his meticulous dissections and craniofacial reconstructions in the mid-20th century. Although Tessier’s primary focus was reconstructive rather than cosmetic surgery, his work clarified the layered organization of the face and demonstrated that facial tissues could be elevated and repositioned safely along natural anatomical planes. This insight was critical: it suggested that durable facial movement required respect for deep structural layers rather than reliance on skin tension alone.

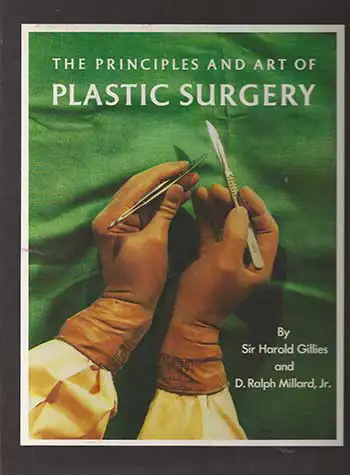

Building directly on Tessier’s anatomical discoveries, Vladimir Mitz, one of Tessier’s trainees, recognized the broader implications of these planes for facial rejuvenation. Mitz later trained under Ralph Millard, gaining further exposure to aesthetic surgery and facial balance. Synthesizing Tessier’s anatomical groundwork with Millard’s aesthetic sensibilities, Mitz collaborated with Martine Peyronie to formally describe and name the Superficial Musculo-Aponeurotic System (SMAS) in 1976.

The 1976 publication by Mitz and Peyronie transformed an implicit anatomical understanding into a clearly defined, reproducible surgical layer. By identifying the SMAS as a continuous fibromuscular sheet linking the facial mimetic muscles to the dermis, they provided surgeons with a precise structure that could be elevated, repositioned, or modified during facelift surgery. This discovery resolved many limitations of earlier techniques by offering a stable deep layer capable of supporting facial redraping while preserving natural expression.

Importantly, the SMAS concept did not emerge in isolation. It represents a direct intellectual lineage: Tessier’s pioneering dissections revealed the planes, Mitz recognized their relevance to facial aging, and, together with Peyronie, translated that knowledge into a formal anatomical and surgical framework. The publication unified reconstructive anatomy with aesthetic application and permanently altered facelift surgery, enabling the development of SMAS lifts, deep-plane facelifts, and composite techniques that remain foundational in modern facial rejuvenation.

The introduction of SMAS plication, imbrication, and lateral SMASectomy in the late 1970s and early 1980s rapidly displaced skin-only facelifts, marking a decisive shift toward anatomically based facial rejuvenation. These techniques allowed surgeons to manipulate the Superficial Musculo-Aponeurotic System (SMAS) rather than relying on surface tension, producing results that were more natural in expression, longer lasting, and less prone to the telltale stigmata of earlier facelifts. By redistributing lift forces to a deeper, more durable layer, surgeons could achieve improved midface elevation, jawline definition, and neck contour while minimizing skin traction and scar distortion.

This new generation of SMAS-based techniques was systematized and popularized by influential surgeon-authors such as Thomas Rees and John Wood-Smith. Through landmark textbooks including Cosmetic Facial Surgery and Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Rees and Wood-Smith translated emerging SMAS concepts into clear, teachable operative methods. Their texts did not merely describe techniques; they provided step-by-step frameworks, anatomical rationale, and complication management strategies that could be reliably adopted by surgeons in training.

Crucially, Rees and Wood-Smith framed SMAS manipulation as a continuum of options, from plication and imbrication to selective SMAS excision, allowing surgeons to tailor the operation to individual facial anatomy and degrees of aging. This pragmatic approach accelerated widespread adoption and integration into residency and fellowship curricula. As a result, SMAS-based facelifting became the new standard of care, effectively ending the dominance of skin-only facelifts and ushering in the modern era of facial rejuvenation surgery.

By codifying these techniques in authoritative surgical texts, Rees and Wood-Smith trained generations of plastic surgeons and cemented SMAS surgery as the intellectual and technical foundation upon which contemporary facelift variations such as deep-plane, extended SMAS, and composite techniques that would continue to evolve.

Perhaps the most accomplished students of Sir Harold Gillies is Dr. D. Ralph Millard, Jr. In addition to co-authoring with Gillies the most famous plastic surgery textbooks, The Art and Principles of Plastic Surgery, Dr. Millard made a deceptively simple yet profoundly influential contribution to the evolution of the modern facelift when he described the surgical removal of submental and cervical fat as a distinct component of facial rejuvenation in the late 1960s.

At a time when facelift surgery focused primarily on skin redraping and, later, deeper tissue repositioning, Millard recognized that excess and malpositioned fat in the neck was a primary driver of aging contour, particularly in the loss of a defined cervicomental angle. By directly addressing fat rather than merely tightening overlying tissues, Millard introduced a principle that now underlies virtually every contemporary neck lift and lower facelift: that volume reduction in the wrong places is just as important as volume restoration in the right ones. His work laid the conceptual groundwork for the later integration of liposuction, direct fat excision, and anatomical neck sculpting into facelift surgery, making a sharply contoured neck as essential to facial rejuvenation as midface elevation or SMAS manipulation.

Dr. Millard continued his esteemed career, often regarded as the world’s greatest plastic surgeon of our time, he published another text, Principlization, that is treasured by plastic surgeons world-wide.

D. Ralph Millard, Jr., M.D.

Deep-Plane and Midface Era (1980s–2000s)

By the late 20th century, facelift surgery entered a phase of profound anatomical and conceptual expansion. Surgeons increasingly recognized that durable facial rejuvenation required addressing the midface, skeletal attachments, and deep soft-tissue planes, not merely the lower face or superficial layers. Advances in endoscopic technology, subperiosteal dissection, and deep-plane anatomy converged to redefine the facelift as a three-dimensional operation focused on restoring youthful facial architecture. This era marked the maturation of facelifting into a comprehensive, anatomically driven discipline—one that integrated depth, volume, and biomechanics to achieve more natural and lasting results.

Oscar M. Ramirez expanded the anatomical frontier of facial rejuvenation by developing the subperiosteal midface lift, frequently performed with endoscopic assistance, during the late 1980s and 1990s. Ramirez recognized that many of the most visible signs of facial aging, such as flattening of the cheeks, deepening of the nasolabial folds, and elongation of the lower eyelid—were rooted not in superficial soft tissues alone, but in descent of the midface as a unit from its skeletal attachments.

By operating in the subperiosteal plane, directly on the facial bones, Ramirez elevated the entire midfacial soft-tissue envelope including muscle, fat, and periosteum as a single composite structure. This approach allowed true vertical repositioning of the malar fat pad and cheek tissues back to their youthful, skeletal-based position. Unlike traditional facelifts, which primarily addressed the lower face and jawline, the subperiosteal midface lift directly corrected central facial aging, restoring cheek projection and softening the eyelid–cheek junction.

Endoscopic assistance was central to Ramirez’s technique. The endoscope provided enhanced visualization through small incisions, enabling precise release of periosteal attachments and controlled elevation of tissues while minimizing surgical trauma. This combination of deep-plane anatomy and minimally invasive access reduced visible scarring and helped preserve facial nerve function, while achieving changes that were otherwise difficult to accomplish with skin-only or SMAS-based techniques.

Ramirez’s work was conceptually significant because it reframed facial aging as a skeletal-based problem, reinforcing the idea that durable rejuvenation requires repositioning tissues relative to bone, not merely tightening surface layers. His subperiosteal midface lift influenced subsequent developments in endoscopic facial surgery and contributed to the broader movement toward anatomically driven, three-dimensional facial rejuvenation strategies that remain integral to modern practice.

Luis Vasconez, MD, revolutionized facial rejuvenation by pioneering the use of the endoscope for forehead and brow lifting, fundamentally changing how surgeons approached the upper face. Introduced and refined during the late 1980s and early 1990s, Vasconez’s work applied minimally invasive technology that was already transforming abdominal and orthopedic surgery to aesthetic facial procedures. This innovation represented a major departure from traditional coronal brow lifts, which required long scalp incisions and were associated with visible scarring, alopecia, and prolonged recovery.

By using an endoscope, Vasconez enabled surgeons to perform forehead lifts through small, strategically placed incisions hidden within the hair-bearing scalp. The endoscope provided magnified visualization of deep anatomical structures, allowing precise release of retaining ligaments, selective muscle modification, and controlled elevation of the brow and forehead tissues. This enhanced visualization not only improved surgical accuracy but also reduced the need for extensive dissection, making the procedure significantly less invasive than earlier techniques.

The impact of Vasconez’s endoscopic approach extended beyond aesthetics. Reduced incision length translated into less scarring, diminished sensory nerve injury, lower rates of alopecia, and faster patient recovery, broadening the appeal of brow lifting to younger patients and those previously hesitant to undergo surgery. Conceptually, his work reinforced a growing trend in facial plastic surgery: that effective rejuvenation could be achieved by targeted anatomical release and repositioning, rather than wide exposure and excision.

Vasconez’s contributions also helped legitimize endoscopic techniques across facial rejuvenation more broadly, influencing subsequent minimally invasive approaches to the midface and neck. By demonstrating that technology could enhance both outcomes and patient safety, he helped usher facial plastic surgery into a modern era where precision, visualization, and reduced morbidity became defining principles.

Dr. Paul Howard & Dr. Luis Vasconez

In 1990, Sam Hamra introduced the deep-plane rhytidectomy, a transformative approach that fundamentally redefined facial rejuvenation surgery. Rather than separating skin from the underlying support structures, Hamra elevated the skin, SMAS, and underlying fat as a single composite unit, preserving their natural anatomical relationships. This method directly addressed one of the persistent shortcomings of earlier SMAS techniques: the tendency to lift the face without adequately correcting midface descent or restoring youthful facial fullness.

By dissecting beneath the SMAS and releasing key retaining ligaments, the deep-plane facelift allowed vertical repositioning of the midface, improving the nasolabial folds, malar contour, and jowls without placing excessive tension on the skin. Because the lift forces were borne by deep structures rather than the dermis, results appeared more natural, with improved longevity and fewer stigmata of surgery. Hamra’s technique represented a philosophical shift from tightening to anatomical restoration, emphasizing youthful shape and proportion over surface smoothness.

In 1995, Hamra further advanced this concept with the description of the composite facelift, extending the deep-plane principles to the eyelid–cheek junction. By lifting the orbicularis oculi muscle in continuity with the midface, the composite facelift restored youthful eyelid–cheek anatomy and midface volume; areas notoriously resistant to traditional facelift methods. This approach corrected the hollowed, skeletonized appearance that often-followed conventional lower blepharoplasty and repositioned descended malar fat to its youthful location.

Together, Hamra’s deep-plane and composite facelift techniques marked a decisive evolution toward three-dimensional facial rejuvenation. His work integrated soft-tissue volume, ligament release, and layered anatomy into a cohesive operative strategy, influencing an entire generation of surgeons and establishing deep-plane facelifting as one of the most sophisticated and durable methods in modern aesthetic surgery.

Meanwhile, surgeons such as J. Peter Stuzin, David C. Baker, Harlan Gordon, and Raul González-Ulloa refined the understanding of facial fascial anatomy and facelift biomechanics, helping to explain why certain facelift techniques succeeded while others failed. Their collective work shifted the conversation from simply where to cut to how forces are transmitted through facial tissues. By studying the SMAS, retaining ligaments, vectors of lift, and zones of fixation, these surgeons clarified how tension could be redistributed away from the skin and toward deeper, more stable structures while improving both natural appearance and longevity of results.

Stuzin emphasized the importance of vector control and selective SMAS release, demonstrating that effective rejuvenation depends on matching lift direction to patterns of facial descent. Baker and Gordon contributed to the refinement of extended SMAS and deep-plane concepts, highlighting the biomechanical advantages of broader fascial mobilization with limited skin tension. González-Ulloa, whose work bridged reconstructive and aesthetic surgery, reinforced the principle that facial rejuvenation must respect underlying anatomy and balance, rather than impose uniform tightening. Together, these surgeons helped codify facelifting as an operation governed by biomechanics and anatomy, not merely by incision design.

At the same time, a parallel evolution was occurring in incision strategy. Short-scar facelift techniques including the MACS lift, S-lift, and S-Plus lift merged as modern descendants of Raymond Passot’s early preauricular designs. These techniques minimized posterior and occipital incisions while relying on vertical or oblique suspension sutures placed in the SMAS to achieve lift. By shortening scars and reducing dissection, they appealed to patients seeking quicker recovery and less visible evidence of surgery.

Importantly, these short-scar approaches did not represent a rejection of earlier principles, but rather a selective application of them. They combined Passot’s insight into concealed preauricular incisions with the late-20th-century understanding of SMAS biomechanics articulated by Stuzin and his contemporaries. While not suitable for all patients, MACS and related lifts demonstrated that, when anatomical vectors are respected, meaningful rejuvenation can be achieved with limited incisions; underscoring how advances in anatomical knowledge continue to reshape the surgical expression of the facelift.

The Facial Volume Revolution with the Modern Facelift

Within the era of facelift, unveiled the challenge of facial volume and the restoration of volume loss due to injury, birth defect, or aging: fat grafting. The modern integration of fat grafting into facelift surgery is inseparable from the work of Dr. Sydney R. Coleman, whose landmark publication, Structural Fat Grafting (2004), fundamentally redefined how surgeons understand and use autologous fat.

Coleman demonstrated that fat was not merely a filler but a living tissue capable of long-term survival, structural support, and biological regeneration when harvested, processed, and reinjected in precise micro-aliquots. By introducing a standardized method of atraumatic harvesting, centrifugation, and layered placement, Coleman transformed fat transfer from an unpredictable adjunct into a reproducible reconstructive and aesthetic tool.

This innovation directly paved the way for facial fat grafting to become a central component of modern facelift surgery, allowing surgeons to address the volumetric deflation that accompanies facial aging, particularly in the midface, temples, and periorbital regions, rather than relying solely on tissue tightening. As a result, contemporary facelifts increasingly combine lifting with volumetric restoration, producing results that are not only more youthful but also more anatomically faithful and durable.

Contemporary Facelifting (2000s–Present)

Modern facelifting reflects more than a cosmetic pursuit; it represents the continued evolution of reconstructive principles applied to facial aging. Contemporary techniques integrate fat grafting, selective ligament release, and nuanced soft-tissue repositioning, often complemented but not replaced by adjunctive modalities such as fillers, lasers, and chemical peels. Although rhytidectomy has long been categorized as cosmetic surgery, its progression clearly traces back to advances in reconstructive anatomy, biomechanics, and tissue handling.

In recent decades, pharmaceutical and device corporations have exerted enormous influence over aesthetic medicine, shifting a substantial portion of facial rejuvenation away from the scalpel and toward proprietary technologies and injectable products. Temporary dermal fillers, frequently marketed under the umbrella of the “liquid lift,” can simulate aspects of facial elevation through volumization and contour enhancement, yet they do not reposition descended tissues and require repeated treatments to maintain effect. Similarly, energy-based lasers and radiofrequency devices promise non-surgical lifting through dermal tightening and collagen remodeling, while thread lifts attempt mechanical suspension using barbed sutures with limited longevity and variable outcomes. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has further entered the aesthetic landscape as a biologic adjunct aimed at improving skin quality rather than achieving true structural lift and perhaps add an additional element to improving post-operative recovery.

Running parallel to this non-surgical, consumption-driven shift, however, is a quieter but critically important line of continued surgical research and experimentation: the refinement of endoscope-assisted facial rejuvenation as a less invasive yet durable alternative to traditional open facelifting. Unlike injectables or energy-based devices, endoscopic approaches preserve the fundamental goals of rhytidectomy through anatomical release, repositioning, and fixation of facial tissues while reducing incision length, soft-tissue trauma, and recovery time. Ongoing exploration of endoscopic access to facial planes reflects an effort to reconcile modern patient demand for reduced invasiveness with the surgical reality that lasting facial rejuvenation requires manipulation of deep anatomy.

Taken together, contemporary facelifting exists at a crossroads. On one side lies an expanding market of temporary, repeatable, technology-driven treatments shaped largely by corporate economics. On the other remains surgical rhytidectomy that remains the only modality capable of reliably restoring facial structure. The future of facelifting will not be defined by abandoning surgery, but by continuing to evolve it, guided by the same reconstructive principles that have driven its progress for more than a century.

The Future & Surgical Art of Facelift: From Experimentation to Refinements

The history of facelifting is not a linear march toward cosmetic refinement, but a layered evolution rooted in reconstructive anatomy, surgical ethics, and an ever-deepening understanding of facial structure. From early excisional skin procedures to anatomically based deep-plane and SMAS techniques, each advance emerged in response to the limitations of its predecessors. What distinguishes modern facelifting is not novelty alone, but the cumulative integration of anatomical insight, biomechanical reasoning, and respect for facial identity and principles that were forged through decades of experimentation, failure, and refinement.

As aesthetic medicine continues to expand under the influence of technology, pharmaceuticals, and consumer-driven models, surgical facelifting remains uniquely positioned as the only modality capable of restoring deep facial anatomy in a durable and reproducible way. Contemporary innovations, whether in volumetric restoration, ligament release, or endoscope-assisted access, do not represent a departure from facelifting’s past, but rather its logical continuation. Understanding where facelifting has come from is essential to guiding where it goes next. Only by anchoring future innovation in historical context and anatomical truth can the facelift continue to evolve as both a surgical art and a reconstructive science.

Facelift not a vanity procedure, but a sophisticated anatomical discipline shaped by science, culture, and human identity.

About the Author

Dr. Paul S. Howard is a retired, board-certified plastic surgeon who specialized in both reconstructive and cosmetic plastic surgery procedures. Over the course of his career, he earned national recognition for his surgical skill, commitment to patient care, and contribution to the advancement of plastic surgery techniques. Dr. Howard received world-class training under two legendary pioneers in the field: Dr. Ralph Millard, a leader in cleft and craniofacial surgery, and Dr. Paul Tessier, widely regarded as the father of modern craniofacial surgery. Their influence helped shape Dr. Howard’s meticulous, patient-focused approach to surgery and deepened his lifelong passion for medical history, especially the history of plastic surgery.

Dr. Ralph Millard & Dr. Paul S. Howard